Poetry

A selection of poems from Granny Scarecrow

Vertigo

Mind led body

to the edge of the precipice.

They stared in desire

at the naked abyss.

If you love me, said mind,

take that step into silence.

If you love me, said body,

turn and exist.

Clydie is Dead!

Our lar, our little mammal.

Though his last day didn’t believe it.

It kept on moving at its usual heartless pace

over and around a hollow cat-space.

We buried him by the toolshed.

The cat flap wouldn’t believe it,

so we sealed its chattering mouth.

We seized and scrubbed his feeding bowls

and sent them to a far shelf.

The fact is, nothing in the house could bear it

when Clyde dropped out of himself...

who waxed loquacious on the subject of roast meat

and cat’s rights, who took favours

from my fingers at mealtimes as just deserts,

who always kept his dress-shirt spinnaker-white

while extending an urgent tongue to his tabby parts;

who reserved for himself, every morning,

a place on a lap, whereon for a while he might

subdue a human; upon whose face

the cat-painter’s brush had slipped a little

applying the Chinese white; for which he received

in compensation, huge Indonesian eyes -

polished jet in a setting of crinkled topaz;

whose tail was so long he could wrap himself up in it;

who could fill with his length, without exertion,

the entire shelf over the radiator;

who was adept at the art of excretion,

and discreet as to the burying of personal treasure.

Dear, wise Clyde, who after tyrannical Bonnie died,

thrived in her absence, Hadrian after Domitian,

you will never again rule us by vocative law,

or pull back the bedclothes at six with a firm paw,

or bemoan the indignities of travelling by car,

or flourish an upright tail on crepuscular walks,

no, nor compile statistics on the field mice of Wales.

Pwllymarch was your chief estate,

you whom Oxford made and Cambridge unmade,

though Hay-on-Wye and Durham made you great.

Much travelled, valuable, voluble Clyde,

who said so much, yet never spoke a word,

requies cat.

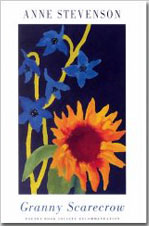

Granny Scarecrow

Tears flowed at the chapel funeral,

more beside the grave on the hill. Nevertheless,

after the last autumn ploughing,

they crucified her old flowered print housedress

live, on a pole.

Marjorie and Emily, shortcutting to school,

used to pass and wave; mostly Gran would wave back.

Two white Sunday gloves

flapped good luck from the crossbar; her head’s plastic sack

would nod, as a rule.

But when winter arrived, her ghost thinned.

The dress began to look starved in its field of snowcorn.

One glove blew off and was lost.

The other hung blotchy with mould from the hedgerow, torn

by the wind.

Emily and Marjorie noticed this.

Without saying why, they started to avoid the country way

through the cornfield. Instead they walked

from the farm up the road to the stop where they

caught the bus.

And it caught them. So in time they married.

Marjorie, divorced, rose high in the catering profession.

Emily had children and grandchildren, though,

with the farm sold, none found a cross to fit their clothes when

Emily and Marjorie died.